A seine boat hauls in part of the record catch in 2010

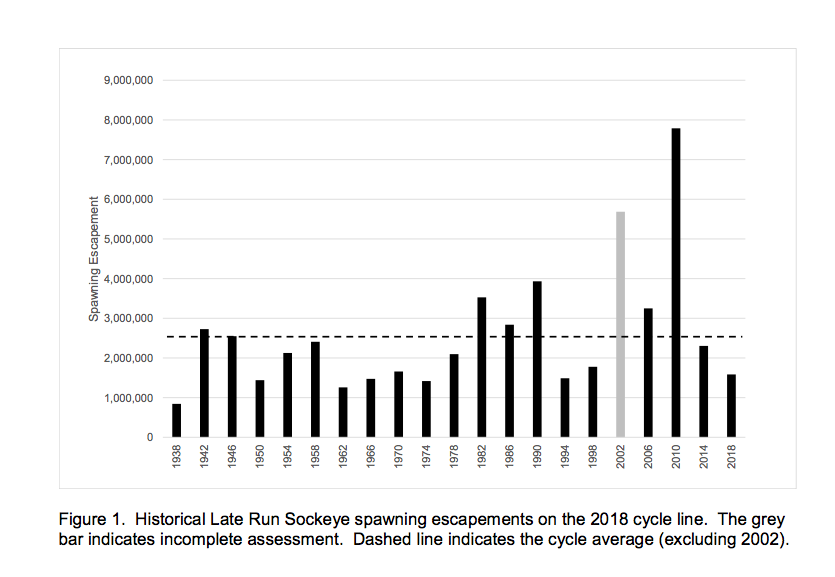

The results are in for the iconic Adams River salmon run that show a very disturbing, sharp decline in spawning numbers. On February 8th, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO is still the acronym) released the near final estimate for the 2018 late Fraser River run that shows only 535,564 sockeye returned to spawn in the Adams, far short of the predicted return and just 34 percent of the average return for this dominant cycle. It was the lowest on record.

Large chinook salmon like this one now rarely make it up the Shuswap River

Ironically, while the Adams River salmon run has declined steeply since 2010, the number of sockeye spawning in the Shuswap River has increased, with 645,209 spawners last year, which is 31 percent above the cycle year average. Despite the increased numbers in the Shuswap River, the overall return of 1,517,301 sockeye to the entire Shuswap region was only 63 percent of the average return. As well, the Kingfisher Interpretive Centre, which operates a chinook salmon hatchery, reports that the average size and weight of the fish that return to spawn has been decreasing and so has the number of eggs.

Greg Taylor, the Senior Fisheries Advisor with Watershed Watch Salmon Society, crunched all the information provided by the three responsible management agencies (Pacific Salmon Commission, Fraser River Panel and DFO) into a spreadsheet that shows the details missing from the government’s report. While the pre-season expectation was 7.4-million, the majority of the fishing decisions were based on a 6-million run estimate, which was scaled back to the final estimate of 4.7-million after fishing was concluded. The final total return (catch plus spawners) was only 4.27-million of which nearly 2.7-million fish ended up in fishing nets.

Greg Taylor, the Senior Fisheries Advisor with Watershed Watch Salmon Society, crunched all the information provided by the three responsible management agencies (Pacific Salmon Commission, Fraser River Panel and DFO) into a spreadsheet that shows the details missing from the government’s report. While the pre-season expectation was 7.4-million, the majority of the fishing decisions were based on a 6-million run estimate, which was scaled back to the final estimate of 4.7-million after fishing was concluded. The final total return (catch plus spawners) was only 4.27-million of which nearly 2.7-million fish ended up in fishing nets.

Fish that should have been allowed to spawn ended up in nets instead

Fish that should have been allowed to spawn ended up in nets instead

Greg Taylor provided more analysis, “They were aware of the uncertainty and risk inherent in estimating how many late summer sockeye were delaying in the Gulf. Even understanding this risk they decided to reduce the ‘management adjustment’ (the number of sockeye added to escapement targets to account for in-river mortality) to near zero. This both decreased any buffer they had against such over-estimations and increased the number of fish (at least on paper) available to harvest.”

At the heart of the issue is the management direction, which dictates a goal of maximizing the harvest while playing lip-service to the sustainability of the population, despite the recognition that the all of the late run sockeye conservation units are listed with the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada as either “endangered”, “threatened” or of “special concern.”  The Pacific Salmon Commission is a joint Canada-U.S. management agency that conducts test fisheries to estimate the run size. It provides the data and their recommendations to the Commission’s Fraser River Panel, which is responsible for designing and implementing the fisheries.

The Pacific Salmon Commission is a joint Canada-U.S. management agency that conducts test fisheries to estimate the run size. It provides the data and their recommendations to the Commission’s Fraser River Panel, which is responsible for designing and implementing the fisheries.

Last year the Panel, which is dominated by salmon fishermen, exceeded their planned “allowable exploitation rate” of over 58 percent on late-run sockeye, with a final rate of 63 percent. Consequently, only 1,584,580 late summer sockeye returned to spawn, which was just 63 percent of the dominant cycle average. It was only luck, not good management that the harvest was not greater and the damage to the population more severe, as they were prepared to catch 3.5-million sockeye if they had been able to find the numbers.

Last year the Panel, which is dominated by salmon fishermen, exceeded their planned “allowable exploitation rate” of over 58 percent on late-run sockeye, with a final rate of 63 percent. Consequently, only 1,584,580 late summer sockeye returned to spawn, which was just 63 percent of the dominant cycle average. It was only luck, not good management that the harvest was not greater and the damage to the population more severe, as they were prepared to catch 3.5-million sockeye if they had been able to find the numbers.

Visitors to the Adams River in October witnessed fewer salmon

Visitors to the Adams River in October witnessed fewer salmon

All species of salmon are already struggling due to the impacts of climate change, loss of habitat, and fish farms that bring diseases and sea lice. One would think that the management direction should be pre-cautionary and focused on conservation to rebuild the stocks, yet the overall goal continues to be exploitation and the result appears to be a steady decline towards extinction. Industry and DFO managed the northern cod to extinction and now it appears they are repeating the same mistakes on the West coast.

To reverse the downward spiral, managers need to change the pattern of exploitation that began when the first canneries were built on the coast at the beginning of the last century and learn from the way First Nations successfully managed salmon populations for thousands of years. Ideally they need to phase out indiscriminate ocean fishing and re-introduce known-stock fisheries, which harvest large proportions of the fish near their spawning grounds. When combined with improved compliance monitoring and accurate counting, known-stock fisheries ensure enough fish return to spawn to sustain the stocks before fishing commences.

To reverse the downward spiral, managers need to change the pattern of exploitation that began when the first canneries were built on the coast at the beginning of the last century and learn from the way First Nations successfully managed salmon populations for thousands of years. Ideally they need to phase out indiscriminate ocean fishing and re-introduce known-stock fisheries, which harvest large proportions of the fish near their spawning grounds. When combined with improved compliance monitoring and accurate counting, known-stock fisheries ensure enough fish return to spawn to sustain the stocks before fishing commences.

POSTSCRIPT

Most of the Fraser River late summer run sockeye return to the Shuswap with only 4 percent returning to the other six runs, including Cultus Lake, Harrison Lake creeks, and the middle Fraser. The return to all but one of these small runs was even more discouraging. For example, only 504 fish returned to the endangered Cultus Lake spawning grounds, which was just 3% of the normal cycle average. These smaller runs are heavily impacted by the indiscriminate ocean net fishing, because the potential spawners are mixed in with the massive numbers of fish returning to the Shuswap.

This column also forms part of a media release by the Watershed Watch Society and the Shuswap Environmental Action Society. As a result of the media outreach, Greg Taylor was interviewed on CBC for the Kamloops morning show and the next day, they interviewed Jennifer Nener from DFO, who is also the chair of the Fraser River Panel. She dismissed the concerns about overfishing and insisted the low return was close to what they estimated and thus was not a problem. She emphasized the difficulty in estimating run sizes due to the salmon’s recent to remain holding in the gulf, rather than moving up the river as they did in the past.

Of course, the chair of the panel would be the last person to admit that they would be allowing the run to be overfished and it is here job to allay any concerns the public has about declining numbers. When you look at the graph, it is easy to dismiss the low return, because there were so many other years with similar returns. The reality is that the trend is a downward one, and the few years when there were massive returns, like in 2010, were anomalies for which there is no explanation.

It certainly is possible that four years from now we could see another large one. However, it is even more likely, given there are now fewer eggs to hatch in the river, and the fishing pressures and climate change impacts; that the next dominant run will be smaller yet. As long as DFO focuses on maximizing harvests and the decisions about harvesting quotas are determined by those doing the harvesting, we will never see any changes to the management direction and more than likely there will be a steady decline in numbers.

Visit the Shuswap Environmental Action Society website to access all the details described in this article and hear CBC interviews with the Greg Taylor and the co-chair of the Fraser Basin Panel. (scroll down to find the links.

There were a massive number of dead salmon that were washed up on the beach near the mouth of the Adams River in 2010. All these salmon decomposed and help to feed the plankton, which become rich food source for the fry that spent a year in Shuswap Lake before heading down the river and out into the ocean.