This sketch of a weir is from Dawson’s 1891 Notes on the Shuswap People and was from photo taken of the Nicola River in 1889.

This sketch of a weir is from Dawson’s 1891 Notes on the Shuswap People and was from photo taken of the Nicola River in 1889.

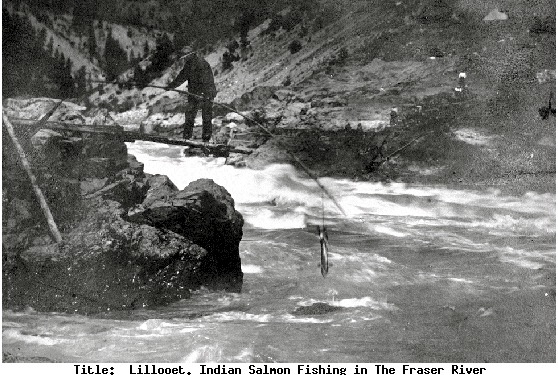

As thousands of people flock to the Adams River to witness another major sockeye run, it is important to reflect on how salmon were fundamental to the lives of the Secwepemc people, as well as the early fur traders who depended on dried salmon to survive the winters. The traditional fishing methods used by the First Nations were both efficient and sustainable, unlike the fisheries that supported the large industrial canneries over 100 years ago.

Scene from large coastal cannery

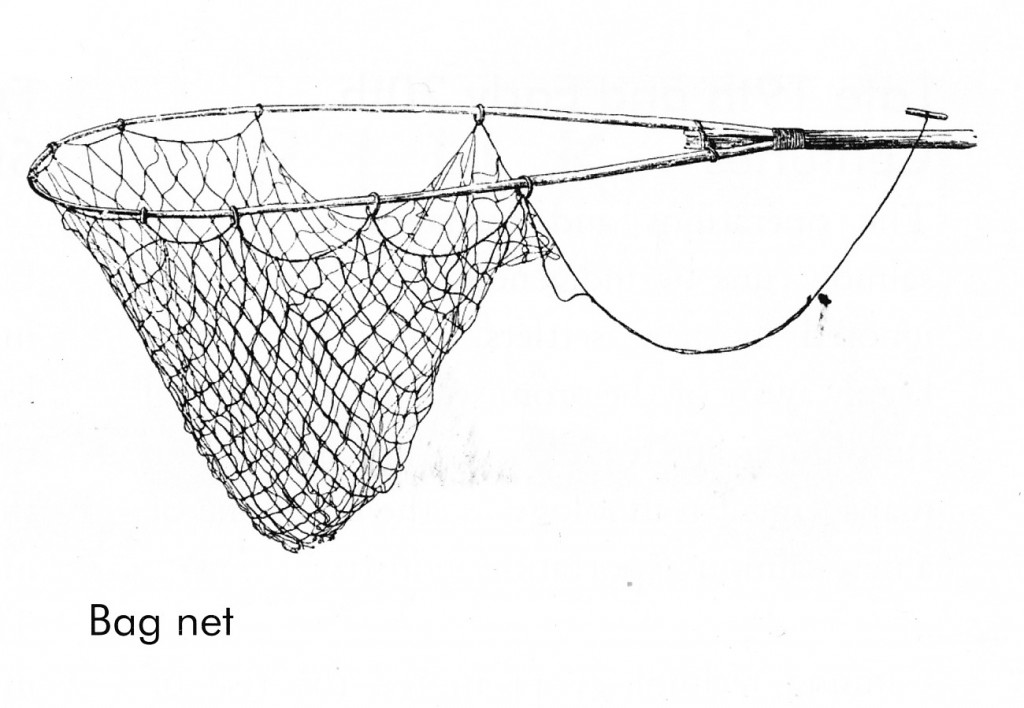

There were a number of fishing techniques used by the local Secwepemc people for thousands of years that required resourcefulness, skill, and cooperation. Along the edge of rivers, men were stationed on projecting rocks above favourable eddies with bag-nets affixed to long poles. The same families occupied these stations and adjoining campsites for many generations according to established cultural traditions.

On smaller streams and side channels, traps and weirs of all descriptions were used. The fence like weirs were made of willow and other sticks lashed together with bark and were stretched across the streams.

This counting station on Scotch Creek operated by the Little Shuswap Lake Band resembles the traditional fish weir.

This counting station on Scotch Creek operated by the Little Shuswap Lake Band resembles the traditional fish weir.

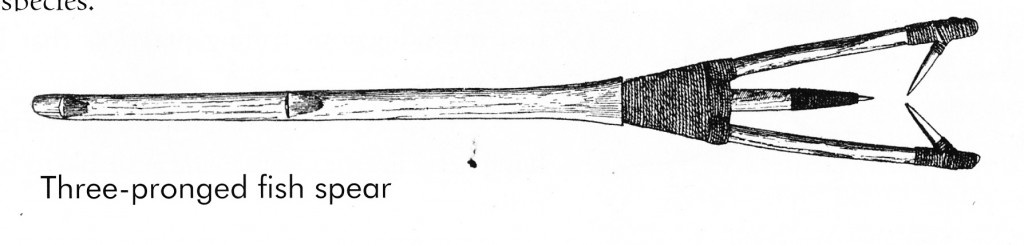

As the salmon attempted to jump over the weir they landed in nets. Elsewhere, catwalks were built above the weirs and men speared and netted the trapped fish. The points on the pronged spears called leisters were fashioned from sharpened antler or splintered animal bone and the fishing nets were woven from hemp twine.

Drawings by James Teit, circa 1900

Drawings by James Teit, circa 1900

They also fished at night in canoes using torches of pitch-soaked wood to attract the spawning salmon. Often a young boy kept the torches burning while the men either speared or netted the salmon out of the water. Family members waited on the shoreline to prepare the salmon for drying after it was caught using knives made from stone.

The Secwepemc were well aware of the need to ensure enough salmon made it to the spawning area to maintain the strength of the run, in contrast to the early settlers, miners and loggers who blocked passage to the fish and damaged habitat. As well, the fishing of individual runs was sustainable, as opposed to netting the fish in the Georgia Strait or the Fraser River, which had the potential to weaken or wipe out specific runs.

The Secwepemc were well aware of the need to ensure enough salmon made it to the spawning area to maintain the strength of the run, in contrast to the early settlers, miners and loggers who blocked passage to the fish and damaged habitat. As well, the fishing of individual runs was sustainable, as opposed to netting the fish in the Georgia Strait or the Fraser River, which had the potential to weaken or wipe out specific runs.

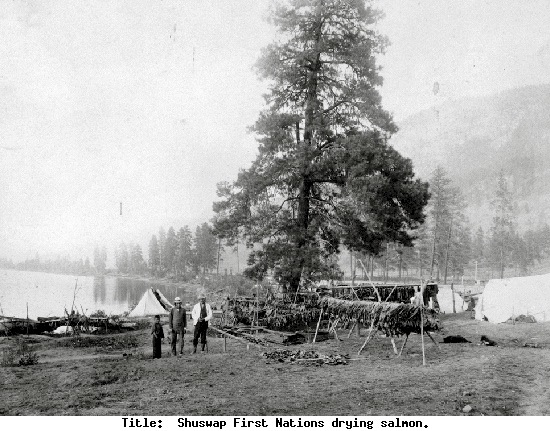

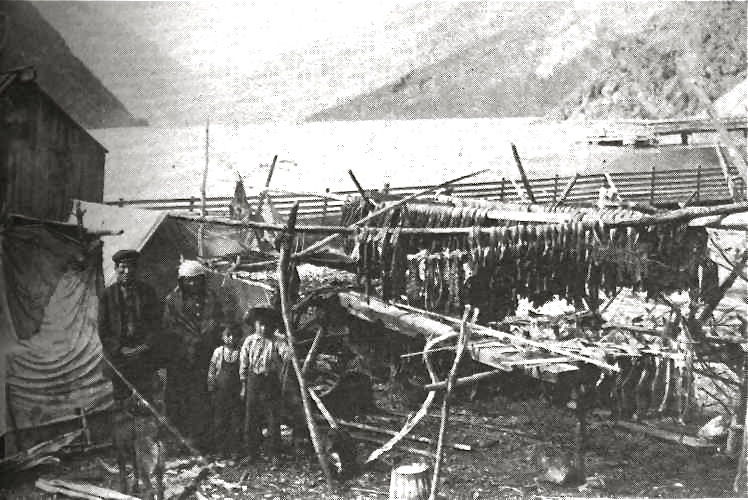

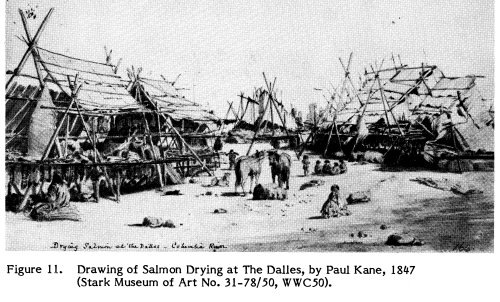

The methods for drying the salmon includied on racks by the sun and wind on racks, by smoke from fires outside or by fires in sweathouse-like structures. The salmon roe was wrapped in bark and buried and the salmon oil was stored in bottles made of fish-skins that were sealed with twine and glue. The dried salmon were stored in underground food caches adjacent to each family’s pit-house or ‘kekuli’ for winter sustenance and were also used for trading with other tribes.

The methods for drying the salmon includied on racks by the sun and wind on racks, by smoke from fires outside or by fires in sweathouse-like structures. The salmon roe was wrapped in bark and buried and the salmon oil was stored in bottles made of fish-skins that were sealed with twine and glue. The dried salmon were stored in underground food caches adjacent to each family’s pit-house or ‘kekuli’ for winter sustenance and were also used for trading with other tribes.

The early British and French fur traders would not have survived if not for the dried salmon. Early records show that the standard allocation was three dried fish per man per day. Thus huge numbers of salmon were needed to supply the trading posts in Kamloops and the Okanagan. By the 1840s and 1850s, there were occasions when by spring First Nations were on the verge of starvation, due in part to poor runs and to over-stocking by the traders.

The early British and French fur traders would not have survived if not for the dried salmon. Early records show that the standard allocation was three dried fish per man per day. Thus huge numbers of salmon were needed to supply the trading posts in Kamloops and the Okanagan. By the 1840s and 1850s, there were occasions when by spring First Nations were on the verge of starvation, due in part to poor runs and to over-stocking by the traders.

Drawing by David Seymour from secwepemc.org

Drawing by David Seymour from secwepemc.org

When the Indian reserves were first established, the government commissioner noted an “exclusive right” for some bands to fish for salmon along the rivers. However, by the 1880s, with thousands of commercial fishermen on the Fraser the competition for fishing was fierce. In 1886, new fisheries regulations were enacted that restricted indigenous peoples’ access to fish. By 1894, the large canneries successfully had lobbied the government to require First Nations to acquire special permission to fish and the new laws defined only European systems as legal fishing gear.

Traditional salmon fishing have been revived. This scene was taken along the Thompson River.

Traditional salmon fishing have been revived. This scene was taken along the Thompson River.

After the disastrous 1913 rockslide at Hells Gate caused by blasting for the Canadian National Railway, the First Nations were further limited and could only catch salmon for personal consumption. Meanwhile, salmon numbers continued to decline due to overfishing, habitat destruction from mining and logging, as well as splash dams built by sawmills on rivers, such as the one built by the Adams River Lumber Company that destroyed the early run on the Upper Adams River that once provided the bulk of the salmon for local Secwepemc people.

The contrast between the greedy, wasteful practices by the commercial fishery and the traditional First Nation fishery was significant. The early ethnographers described the Secwepemc culture as egalitarian because food and fish were shared equally and no families went hungry. Salmon were considered sacred, their cycle was well understood and the traditional fishing methods had ensured the sustainability of the resource for thousands of years before Europeans arrived.

POSTSCRIPT

Recent court rulings in favour of First Nations has allowed a resurgence of salmon fishing in B.C. rivers and lakes. This fall, there was a blend of traditional and commercial fishing techniques when a trawler was used on Kamloops Lake and the fish were sold at a local supermarket.