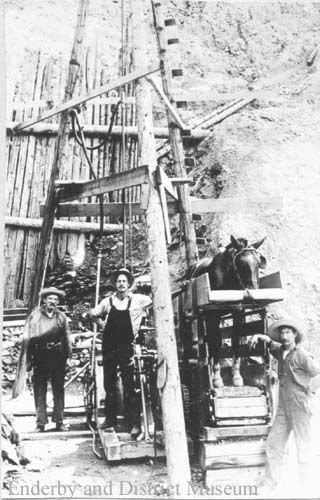

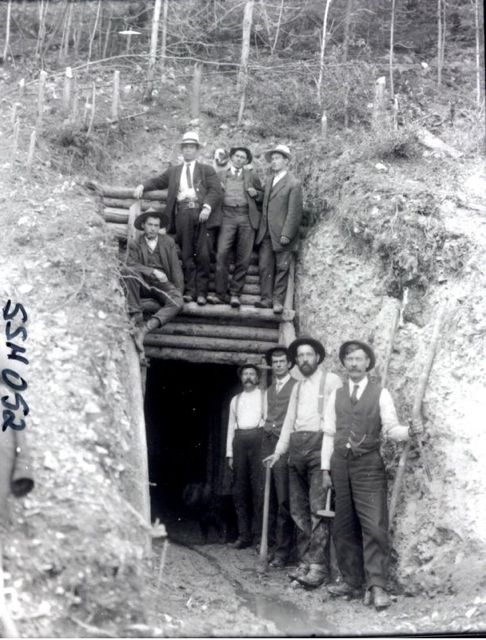

Enderby Coal Mine, circa 1905, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum & Archives

With all the attention currently in British Columbia directed to mining, one might wonder if there will be renewed interest in mineral exploration here in the Shuswap. Up until now, the Shuswap has mostly been considered an area lacking in significant mineralization and certainly there has only been a few successful mining operations to date, including the Samatosum Mine near Adams Lake as described in the previous column and the gypsum mine above Falkland. However, there has been no shortage of mining projects and many of these ventures provide some intriguing stories.

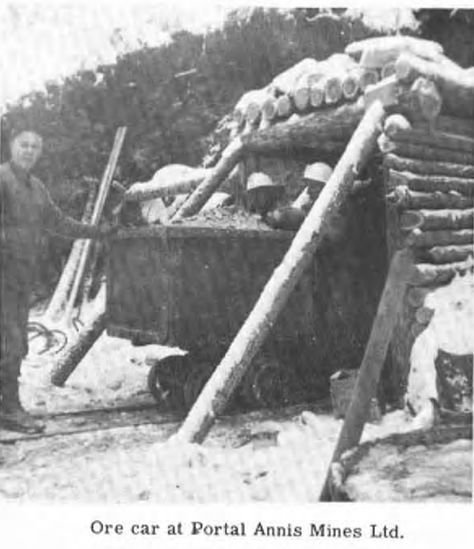

It is often said that most mining ventures are more about penny stock promotion than actual serious mining potential, and that was likely the case for the Annis Mine in the Larch Hills. One can only wonder how many life savings were lost as in 1967, 400 to 500 interested local residents, many of them one of the 364 shareholders, attended a meeting at the site of the mine property to hear glowing accounts of how their money had been wisely invested to develop the lead-zinc mine. Apparently, the 48-metre long abandoned tunnel is still there. The most recent survey, done in 1995, showed miniscule amounts of silver, lead and zinc, that was hardly enough to warrant further interest.

It is often said that most mining ventures are more about penny stock promotion than actual serious mining potential, and that was likely the case for the Annis Mine in the Larch Hills. One can only wonder how many life savings were lost as in 1967, 400 to 500 interested local residents, many of them one of the 364 shareholders, attended a meeting at the site of the mine property to hear glowing accounts of how their money had been wisely invested to develop the lead-zinc mine. Apparently, the 48-metre long abandoned tunnel is still there. The most recent survey, done in 1995, showed miniscule amounts of silver, lead and zinc, that was hardly enough to warrant further interest.

Early settlers in and near Enderby likely thought they would soon have a good source of steady income, when the news came out in 1904 about the discovery of coal by George Weir at the base of a hill seven miles north of the town. The Enderby Coal Syndicate was formed, shares were sold and work began on an initial tunnel. The workings did uncover a 16-foot long seam of coal, but with continued digging all they could find was clay. Despite more tunneling, and drilling, the mother lode eluded them and by 1914, the company was dissolved. One of the original syndicate members, S.F. Tolmie still owned more than 30,000 worthless shares, when he became B.C.’s premier in 1930.

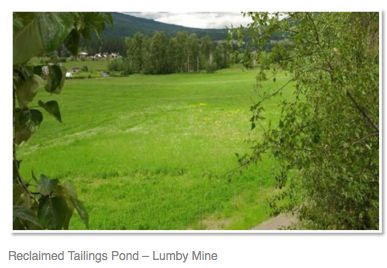

Many Lumby residents once owned shares in the nearby mine on Saddle Mountain, where minerals were first discovered by a local teacher in the early 1900s. Perhaps some of them may have made a few profits as the mine did produce between 1968 and 1974 many tons of ore that produced over 1.5 million grams of silver, 1214 grams of gold along with some copper, lead and zinc. Prospects were still optimistic in 2001, when Quinto Technology Inc. had infrastructure in place to process mica, silica, graphite and pyrite gold. Yet any dreams of future profits were soon dashed, as in 2009 reclamation began at the then abandoned site and when it was completed in 2011, the company received an industrial award for its successful cleanup, tailings pond backfilling and re-vegetation project.

I even once profited from work on a mining scheme, when I was employed to help construct a nearby timber framed unloading ramp for ore removed from the Mosquito King exploration trenches high up in the Adams Plateau. The remains of a large, timbered staff quarters are likely still near there, along with hundreds of core samples. Exploration began as early as 1927 and in 1972, tons of ore was sent to Trail that produced lead and zinc and small amounts of silver and gold, but never enough to make the project worthwhile. Other projects on the plateau included the King Tut, Spar and Lucky Coon sulphide deposits, none of which were lucky.

During photographic trips by airplane to the Upper Seymour wilderness area, before we were successful in creating the provincial park, I saw the Grace Mountain plateau country a few times. There are many small lakes but few trees in this massive alpine area, but I never spotted the remains of the Cotton Belt mine buildings that can be still found there. It is a richly mineralized area, but despite exploration efforts that began as early as 1905, which included shafts being dug and drilling, not enough lead, zinc, copper, silver or gold has ever been found to justify full-fledged mining.

Perhaps the only mining exploration project currently underway in the Shuswap that may one day become a real mine, is at the Ruddock Creek zinc deposit located in the upper Oliver Creek drainage, high above Tum Tum Lake. I went there by helicopter in 2008 for an official tour, including a ride down the one kilometre long tunnel, and was actually impressed, as the staff insisted that environmental impacts from the mining would be minimal, because the acid generating ore is surrounded by alkaline rock that would neutralize the output. However, I have since learned that while the mining may not be a problem, the processing may indeed result in pollution that could threaten the creek and perhaps even the Adams River, downstream. The project also faces stiff opposition from many local First Nation groups.

Ruddock Creek “incline” – tunnel

Ruddock Creek “incline” – tunnel

POSTSCRIPT

There was not room in the column for other Shuswap mining stories. Here is an excerpt from an earlier column about Mt. Ida that describes the old mine located there:

Many people think that Shuswap’s Mount Ida is an extinct volcano because of the volcanic rock and deep holes at the top, but these rocks and holes are what remain from a basalt lava flow that occurred many millions of years ago. It was actually erosion that created the mountain, as underneath the ancient lava is a very hard layer of granitic rock.

Mt. Ida mine, photo by Rex Lingford, circa 1910, photo courtesy of Old Photos.ca and the Salmon Arm Museum and Archives

Mt. Ida mine, photo by Rex Lingford, circa 1910, photo courtesy of Old Photos.ca and the Salmon Arm Museum and Archives

It was this layer of igneous rock that attracted the eccentric mining prospector, Jack Thornton to spend years searching for molybdenum and platinum in the 30’s and early 40’s. Jack dug two tunnels into the mountain and lived there during the winters in a log cabin. He was only seen in town occasionally getting supplies and delivering rock samples for analysis. During the summers he prospected in the North Shuswap on the Adams Plateau and in the Cottonbelt country above Seymour Arm. In 1943, after an extended absence from town, searchers went up the mountain to find that Thornton had passed away. They buried him in one of his tunnels, which they blasted shut to prevent the potential for accidents.

There is also a geocache located at the site of this old mine. Here is the description:

The first mining claim was staked on Mt. Ida in 1899 by a C. Bain who worked the claim with Alphonse Eiman. It had fair showings in silver with a little gold. Many holes were sunk and a small seam of rich ore in silver was found.

A lot of work took place by different claim holders until 1925 when the mine was abandoned. The remains of this mining operation – 2 dark, long shafts and lots of rubble surround the scenery of this cache. Of the two shafts, The left one is still complete, and goes in quite a ways. There is a lot of water dripping in it too. The right one caved in about 20ft in. I suggest that you do NOT ENTER the shafts as they are subject to cave in and really old. Cache is not hidden in the mine shaft.

Miners are a stubborn and persistent lot and refuse to give up! Websites show that efforts still continue at many old mine exploration areas in the Shuswap. At the Cottonbelt, there is a report that describes a drilling and exploration program done as recently as 1996. At the Annis site in the Larch Hills, Matnic Resources, Ltd. did three test drills in 2012 totaling 869 metres. They found some “encouraging” results northwest of the old Annis “adit” or tunnel. Here is the report on the Annis Mine from 1966: Annis mine report.