A look back at land use planning

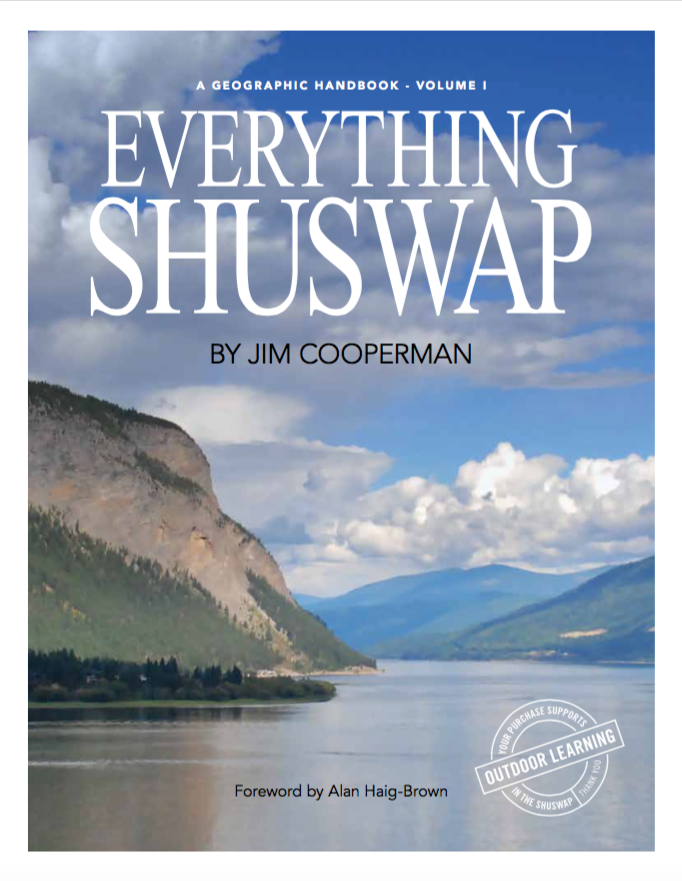

The then proposed Anstey Arm/Hunakwa Lake Provincial Park, photo by Myron Kozak

The then proposed Anstey Arm/Hunakwa Lake Provincial Park, photo by Myron Kozak

The 1990s was a unique decade in British Columbia, when environmental conflicts made headlines and the provincial government responded with environmental legislation and policies, along with intense land use planning processes throughout the province. The dichotomy of jobs versus the environment and parks versus logging were as much a part of the debate in the Shuswap as elsewhere. When the government led process in the form of the Okanagan Shuswap land and Resource Management Planning process (LRMP) began here in 1996, the Shuswap Environmental Action Society (SEAS) was ready.

As the SEAS president, I had participated in the successful Kamloops LRMP, which concluded after just two years with a plan that created new parks in the Adams River region including the Momich Lakes. We had pushed hard for the Shuswap process and when it began, it was thus easy to become frustrated with the glacial pace due to the overwhelming amount of government bureaucracy. The government team had increased the level of complexity to the point of information overload so that it took a few years before all the participants actually began to develop the plan including negotiating the size and locations of the areas to be protected.

The LRMP table met monthly except during the summer, mostly in Kelowna, on a Friday and Saturday. There were approximately 30 stakeholder participants with an equal number of alternates representing resource sectors (logging, mining, trapping and cattle), conservation groups, labour, tourism, commerce, and recreation. Although there were four environmental protection representatives from the Shuswap, North, Central and south Okanagan along with a naturalist, it appeared as if we were outnumbered with so many industry delegates at the table.

We began with a workshop on how to reach consensus with conduct interest-based negotiations to avoid becoming locked into positions early in the process. A key part of the process was determining what the impacts could be to our interests from the plan and in order to determine these impacts it was necessary to undertake a multiple accounts analysis that would provide a comprehensive understanding of the current status of the land base and its many values, and predict the implications of the plan.

A giant cedar tree in the then proposed Upper Seymour Provincial Park

A giant cedar tree in the then proposed Upper Seymour Provincial Park

The many provincial and local government representatives at the table were there to provide information and advise, but they did not participate in the negotiations and final decision-making. There was no shortage of information and we spent over a year hearing reports, studying countless maps, and pouring over data. Key to the process was the goal of representation, as we were attempting to protect at least 12 percent of each type of ecosystem, down to the level of sub-zones. For example, the Interior Cedar-Hemlock forests include eleven subzones from very dry/warm to very wet/cool.

During the summer of 1997, we were tasked to create a “vision” of what we wanted included in the plan. We teamed up with allies: the naturalists, recreation, tourism, Wildlife Federation and trapping representatives, to form the Conservation Sector. After each sector provided presentations that included maps showing our preferences, the government contracted a professional legal mediator to oversee the negotiations. His first task was to create a compromise map, which was a difficult task considering that industry proposed just 54,000 hectares of parks while we proposed 300,000 hectares!

Measuring a huge cedar tree in the then proposed Upper Perry protected area

Measuring a huge cedar tree in the then proposed Upper Perry protected area

The plan we strived for included much more than just new parks, as it contained special management zones for many different wildlife species as well as recreation, added protection for watersheds, specific direction for forestry practices, and recommendations for a follow-up advisory board. A completed land use plan is made up of objectives and strategies for each resource value, that when endorsed by government became legally enforceable under what was then the Forest Practices Code. The process used for the table to actually write the plan was at first unnecessarily slow and cumbersome, until we finally used smaller committees to focus on specific sections.

By the spring of 1999, the negotiations were nearly complete. Much of the work that remained involved reviewing drafts of the plan and making final changes and improvements. I particularly remember one evening when we were in the final negotiations regarding the size and boundaries for certain parks. The conservation sector was in one hotel room and the forest industry was in another upstairs. The mediator, using shuttle diplomacy, would take our proposal up to the industry reps, who stated their preferences and then he would return to hear our responses. By the end of that evening, we had the final compromise and the LRMP was nearly complete.

In the end, the plan created 120,000 hectares of new parks, including 25,000 hectares in the Shuswap. In addition, it added another 10,000 hectares of riparian protection for watersheds, interim protection for 9,000 hectares of critical caribou habitat to allow for research, and 61,000 hectares of old growth management areas that were mapped after the process ended. But industry could not agree to special zones, so instead we created resource-specific zones. Equally important, was that after five years an improved level of respect and trust was generated between all participants that continued for nearly a decade at follow-up LRMP meetings until the provincial government ended these opportunities for dialog and cooperation.

Despite some flaws in the lengthy process, the development of an 8-centimeter thick comprehensive plan by a multi-sector group was a true success story. The monumental task would not have been possible without the foresight and dedication of the B.C. government of the day, who developed the protected area strategy and the land use planning process.

It is one thing to design a system, but to achieve success in implementation; government required effective and able staff. LRMP table members were fortunate to have an excellent government team that kept the process moving ahead as well as great facilitators that pushed us to consensus. Key to the success were all the table members, who dedicated so much of their time to this process and who were able to work effectively towards a final plan that best met all of our interests.