It is an exceptional book about a remarkable man who never received the recognition he deserved for his major input to what was then the new science of anthropology. Written by University of Victoria professor emeritus Wendy Wickwire, At the Bridge, not only describes James Teit’s extraordinary life and achievements, but it also explains how his employers took him advantage of him and why the academic community discounted his vast contributions.

It is an exceptional book about a remarkable man who never received the recognition he deserved for his major input to what was then the new science of anthropology. Written by University of Victoria professor emeritus Wendy Wickwire, At the Bridge, not only describes James Teit’s extraordinary life and achievements, but it also explains how his employers took him advantage of him and why the academic community discounted his vast contributions.

Wickwire begins the book with her own story about how she became fascinated with Teit and describes her many decades of research and writing about both Teit and Indigenous songs and storytelling. In some ways, Wickwire’s work with Indigenous elders carried on from what Teit began, as many of her books are collections of stories that have been passed down from generation to generation.

Teit immigrated to Canada from the Shetland Islands in 1884 at the age of 19 to work for his uncle at his store in Spences Bridge. He was part of a mass exodus of the islands, once ruled by Denmark that was due to deteriorating economic conditions caused in part by the collapse of the fishery and an unfair political and economic system controlled by the wealthy few. Before he left, James was influenced by the Islands’ “free-thinkers” who challenged the establishment, explored their Scandinavian roots and pursued socialist ideals.

Teit (left) and Jimmy Kitty (Nlaka’pamux) on a hunting trip, 1904. Photo by Homer Sargent. Photo courtesy of James M. Teit and Sigurd Teit.

Teit (left) and Jimmy Kitty (Nlaka’pamux) on a hunting trip, 1904. Photo by Homer Sargent. Photo courtesy of James M. Teit and Sigurd Teit.

When the CPR pulled its construction camp out of Spences Bridge after the railway was completed in 1886, his uncle’s store had to close and Teit was forced to find other work. The backcountry skills he developed in the Shetland Islands helped him as he turned to hunting and trapping as a source of income. Within a few years, Teit became a foremost hunting guide and one of his loyal wealthy clients became a benefactor for some of his anthropological studies.

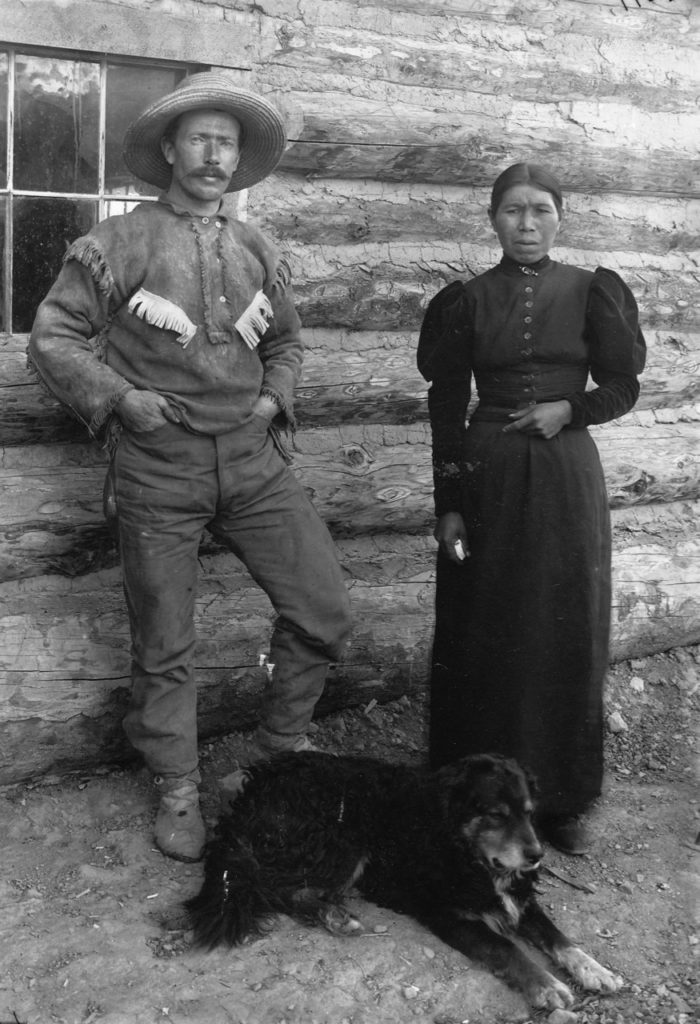

As Wickwire explains, Teit’s connections to Shetland’s Indigenous peoples helped him develop a deep respect for his adopted homeland’s Indigenous peoples that resulted in intense collaboration with them over his lifetime. Although most settlers scorned such unions, Teit’s marriage to Lucy Antko in 1892 further deepened his closeness to the local Nlaka’pamux people and likely helped him become fluent in their language.

As Wickwire explains, Teit’s connections to Shetland’s Indigenous peoples helped him develop a deep respect for his adopted homeland’s Indigenous peoples that resulted in intense collaboration with them over his lifetime. Although most settlers scorned such unions, Teit’s marriage to Lucy Antko in 1892 further deepened his closeness to the local Nlaka’pamux people and likely helped him become fluent in their language.

Teit and Antko at their Twaal Valley cabin in June 1897, photo by Harlan Smith courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History

When the young anthropologist Franz Boas stopped in Spences Bridge in 1894 as part of his ongoing studies of the province’s Indigenous peoples, he met Teit who then helped take cranial measurements. He soon realized that Teit, who had already begun studying Nlaka’pamux culture and history, was the ideal candidate to research and write a complete ethnographic report of the Nlaka’pamux.

Over the following 28 years until his death in 1922, Teit completed 11 monographs, collected hundreds of artifacts, made many wax-cylinder recordings of songs and stories, and produced thousands of pages of unpublished notes and drawings. Only a few of Teit’s ethnographies were published under his name, as much of his work was under-credited and in fact, plagiarized.

Although Boas was both his mentor and major employer, Teit’s research technique and style described as “participant-based” was in sharp contrast to Boas, who remained an aloof observer. While Boas worked to document what he considered to be a dying primitive culture, Teit studied those who he lived with and befriended. Wickwire describes Teit’s work as “an anthropology of belonging,” which is also the sub-title for her book.

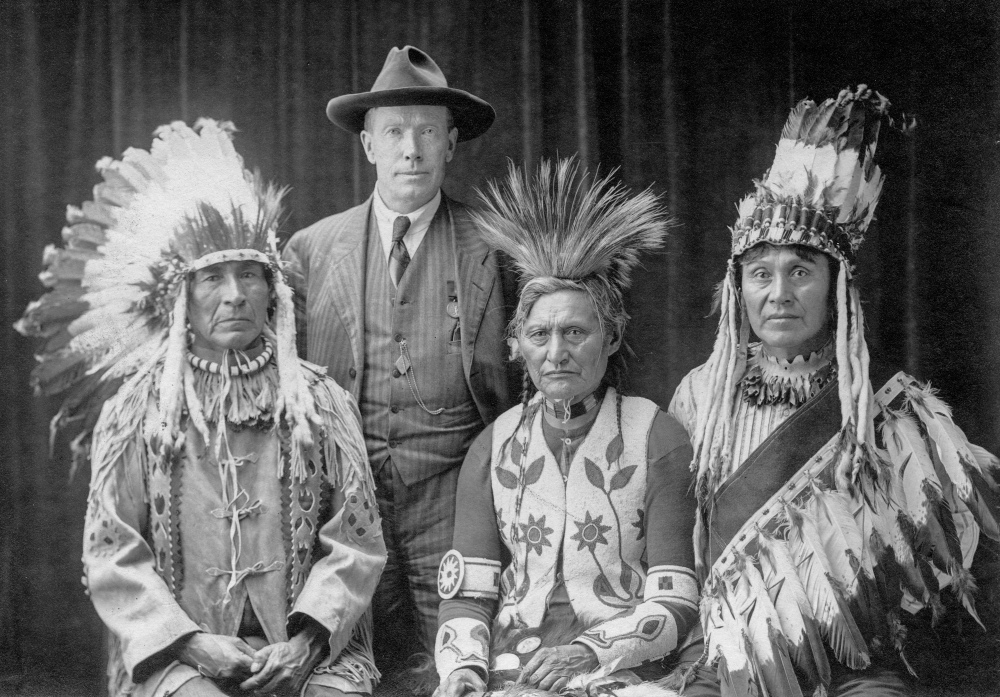

Delegation of chiefs from across Canada in Ottawa to protest before parliament in May 1920, Teit is in second row, second from left, photo courtesy of Sigurd Teit

Delegation of chiefs from across Canada in Ottawa to protest before parliament in May 1920, Teit is in second row, second from left, photo courtesy of Sigurd Teit

As a result of his closeness to the people he studied and his own socialist background, Teit became intricately involved in the Indian Rights movement by actively campaigning for provincial and national organizations, often at his own expense. One of his most significant efforts was assisting the Interior Chiefs prepare the Memorial presented to Prime Minister Laurier in 1910 about the need for justice and fairness so that “wrongs may at last be righted.”

Teit with three Interior chiefs in Ottawa in 1916, photo courtesy of Sigurd Teit

Teit with three Interior chiefs in Ottawa in 1916, photo courtesy of Sigurd Teit

Given that much of what is known today about the history of the Secwepemc stems from The Shuswap, Teit’s seminal monograph, At the Bridge should be of interest to all those who want to learn more about this early ethnographer and B.C.’s Indigenous people. Thanks to Wickwire’s book, more people will become aware of Teit’s many significant achievements, and hopefully his reputation will gain the recognition it deserves.

POSTSCRIPT

One of the most fascinating aspects of Teit’s life for me is his life in the Shetland Islands and how he came to emigrate to Canada, as I find parallels to my own life experiences. Both of us ascribed to radical, non-conformist ideologies that focused on social justice, which were at odds with the prevailing views of the ruling class. Whereas, Teit left Shetland because of the lack of economic opportunity, I left the U.S. to avoid participating in an illegal and immoral war.

After a return trip to Shetland to visit family and friends in 1902, Teit became enamored with socialism and upon his return to B.C., he participated in the Canadian socialism movement. I joined the NDP and worked tirelessly for the environmental movement. Teit studied his Indigenous neighbours and wrote extensively about them. I have studied my home place, the Shuswap, and write extensively about it. He cared deeply about his home place, as do I and both of us worked to make positive changes.

However, unlike myself, in his short lifetime (he died at 58), Teit produced a massive amount of written material and traveled extensively across the province on horseback or by foot. In addition, he operated a ranch and raised a large family. His accomplishments were monumental and he kept going despite the lack of adequate compensation or recognition. He was almost always struggling for money to cover his family’s expenses and almost ruined his eyesight by spending so many hours reading and writing with poor light.

Wickwire only scratched the surface with her comprehensive biography, as Teit was so productive that to adequately tell his whole story would take much more than one book. He was fluent in a number of Indigenous languages and he had established deep personal relationships with so many Indigenous people across the province. He deserves a revered space in Canada’s history and in the history of the science of anthropology. Hopefully, this book will help make that happen.

Learn more about the book and Wendy Wickwire from her website, https://wcwickwire.wordpress.com/

Listen to the CBC interview with Wendy Wickwire – interview