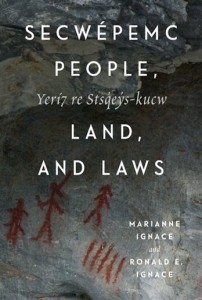

A better understanding of Indigenous peoples is now possible, thanks to the recent publication of Secwepemc People, Land and Laws by Marianne Ignace and Chief Ronald E. Ignace, with contributions from archeologist Mike Rousseau, ethnobotanist Nancy Turner and geographer Ken Favrholdt. Ancient stories, archeological evidence, archival records, ethnographic studies, linguistic research and first-hand knowledge have been masterfully woven together to create this comprehensive examination of the Secwepemc peoples’ ancient connection to the land and the injustices they have endured for over 200 years.

A better understanding of Indigenous peoples is now possible, thanks to the recent publication of Secwepemc People, Land and Laws by Marianne Ignace and Chief Ronald E. Ignace, with contributions from archeologist Mike Rousseau, ethnobotanist Nancy Turner and geographer Ken Favrholdt. Ancient stories, archeological evidence, archival records, ethnographic studies, linguistic research and first-hand knowledge have been masterfully woven together to create this comprehensive examination of the Secwepemc peoples’ ancient connection to the land and the injustices they have endured for over 200 years.

In addition to being the Chief of the Skeetchestn at Deadman’s Creek, Ron Ignace is an adjunct professor at Simon Fraser University and he was fortunate to have been raised by his great-grandparents, whose parents in turn were born in underground homes and were adults before the settlers arrived. Consequently, Ron became fluent in Secwepemctsin at an early age and grew up with a deep respect for his heritage.

In addition to being the Chief of the Skeetchestn at Deadman’s Creek, Ron Ignace is an adjunct professor at Simon Fraser University and he was fortunate to have been raised by his great-grandparents, whose parents in turn were born in underground homes and were adults before the settlers arrived. Consequently, Ron became fluent in Secwepemctsin at an early age and grew up with a deep respect for his heritage.

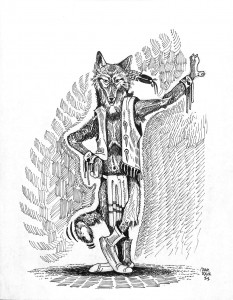

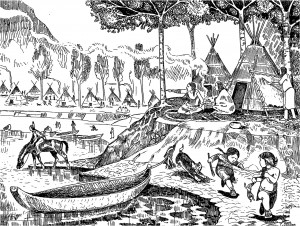

Drawings by David Seymour, Secwepemc Museum and Archives

Drawings by David Seymour, Secwepemc Museum and Archives

The book begins with a look at the geological history as framed by the ancient stories of the transformers, who “tamed the land and made it inhabitable for future generations.” In doing so, the Ignaces have connected the emergence of their nation to the environmental history of the region.

Middle period points, photo by Carryl Armstrong, Secwepemc Museum and Archives

Middle period points, photo by Carryl Armstrong, Secwepemc Museum and Archives

In the chapter on archeology, we learn about the evidence from excavations that indicates human occupation in the Interior Plateau region began over 10,000 years ago. From the earliest days, when there was likely a low population density of small family groups until the Europeans arrived, the history is divided into horizons and phases as determined by the type of stone bifaces (spear points and knives) found.

Key eras include the Lehman Phase, when Coast Salish moved up to the interior about 4,700 years ago; the Shuswap Horizon about 3,000 years ago, when salmon became an important part of the diet; and the Plateau Horizon about 1,600 years ago, when bow and arrow technology was introduced from the Northern Plains.

Certainly, one of the most fascinating aspects of Indigenous culture is that there are so many distinct languages that help to define the numerous, diverse First Nations in the province. The Ignaces estimate that the roots of the Secwepemc language, Secwepemctsin, began some 4,500 years ago and eventually, two dialects emerged, Eastern and Western. There is an intricate structure to the language that connects it to the land and ancient experiences.

Certainly, one of the most fascinating aspects of Indigenous culture is that there are so many distinct languages that help to define the numerous, diverse First Nations in the province. The Ignaces estimate that the roots of the Secwepemc language, Secwepemctsin, began some 4,500 years ago and eventually, two dialects emerged, Eastern and Western. There is an intricate structure to the language that connects it to the land and ancient experiences.

Digging roots, 1898 American Museum of Natural History

Digging roots, 1898 American Museum of Natural History

Unlike the unsustainable misuse of resources that is so common today, the Secwepemc people were true stewards of the land, the plants and the animals. Careful and respectful management of resources was both part of their spiritual beliefs and their culture. Far more than simple hunter-gatherers, the Secwepemc utilized horticultural methods and habitat management practices that were an early form of agriculture. In addition, their egalitarian lifestyle meant that harvests and hunts were always shared and no one went hungry.

The Secwepemc sense of place that evolved over the millennia is intense and can be best understood by how their place names are an integral part of their stories. At one time, there were place names for every location in their territory and these names were derived from the experiences of past generations. Those names that have survived provide reference points to their history and help confirm the Secwepemc ownership of the land that was stolen from them.

Secwepemc Chiefs at New Westminister, circa 1868, Royal BC Museum and Archives

The dispossession of Secwepemc traditional lands that began when Europeans arrived and their resistance to the European occupation is well chronicled. Of great significance is the Memorial presented to Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier in 1910, which describes their history since first contact and describes what should be a respectful relationship between the two nations according to their ancient laws. Described by the Ignaces as the Secwepemc “Magna Carta, the Memorial continues to serve a purpose today as it provides the “underpinnings of Indigenous nationhood.”

Secwepemc youth being hauled away to the residential school in a cattle truck, Joan Arnouse collection, Secwepemc Museum and Archives

Secwepemc youth being hauled away to the residential school in a cattle truck, Joan Arnouse collection, Secwepemc Museum and Archives

One overriding theme throughout the book, is that despite the theft of their land and the attempts to eliminate their language and way of life, the Secwepemc people have managed to maintain and advance their culture thanks in part to their laws and traditions that have passed down from generation to generation. Above all else, the Ignaces have put to rest the misconception that Ingenious Nations were primitive people that were inferior to Europeans, as they clearly show how the Secwepemc indeed had a sophisticated culture and treated each other, their neighbours and the environment with more respect than we see today in our supposedly advanced societies.

POSTSCRIPT

There was not space in the newspaper column for a full review of this most excellent book, which was a joint effort of Ron Ignace and Marianne Ignace who deserves equal recognition. She is a professor of linguistics and First Nation Studies at Simon Fraser University and has authored and co-authored papers in various journals and books on the Secwepemc (Shuswap) people of the Plateau. Her interests are aboriginal land use and occupancy, ethnobotany, traditional ecological knowledge, ethnohistory, and the linguistic and anthropological analysis of Aboriginal language discourse.

There was not space in the newspaper column for a full review of this most excellent book, which was a joint effort of Ron Ignace and Marianne Ignace who deserves equal recognition. She is a professor of linguistics and First Nation Studies at Simon Fraser University and has authored and co-authored papers in various journals and books on the Secwepemc (Shuswap) people of the Plateau. Her interests are aboriginal land use and occupancy, ethnobotany, traditional ecological knowledge, ethnohistory, and the linguistic and anthropological analysis of Aboriginal language discourse.

While for the most part, the Secwepemc were historically a peaceful nation, there were border disputes that resulted in occasional warfare. Disputes were often settled with peace treaties including the famous Fish Lake Accord, which included marrying into the opposing Nation so to consolidate a kinship alliance between the two groups.

While for the most part, the Secwepemc were historically a peaceful nation, there were border disputes that resulted in occasional warfare. Disputes were often settled with peace treaties including the famous Fish Lake Accord, which included marrying into the opposing Nation so to consolidate a kinship alliance between the two groups.

The core productive unit of Secwepemc society was the extended family, which functioned as a flexible, inclusive group. The key aspect of family life was sharing and helping one another as this was necessary given the need for self-sufficiency to survive. The section on genealogy includes lineage charts that trace ancestors back to the late 1600s that were prepared using baptismal records.

While the missionaries may have thought they were converting pagans to Christians, in fact, due to the language barrier the Secwepemc people were interpreting the prayers and practices in terms of their own ancient spiritual beliefs. However, the strict religious instruction in the residential schools did result in the loss of Secwepemc identity and spiritual knowledge.

We also learn much about the dispossession of Secwepemc lands and the many injustices inflicted upon them, after so many people died from smallpox and other diseases. After they were taught to farm the land and became very successful growing crops, the settlers complained about the competition and so the government made it difficult for them to sell their harvest and allowed their water rights to be taken away.

The book chronicles their long history of fighting for their rights, that involved a number of trips to Ottawa and England, where they had one audience with the king that was fruitless. Yet, despite over 150 years of fighting for justice, full and just recognition of Secwepemc title and rights remains unresolved.

There are many insights that can be gained from reading this excellent, comprehensive book, all of which lead to a better understanding and more appreciation of the Secwepemc worldview, which was closely connected to their home place. Learning more about First Nation history is also a key step towards reconciliation.

Woman scraping skin, Kamloops 1898, photo by Harlan Smith, American Museum of Natural History

Woman scraping skin, Kamloops 1898, photo by Harlan Smith, American Museum of Natural History

Addendum

SARAH A. NICKEL

UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN

Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws is one of those books you anticipate long before it’s released and struggle to put down once it arrives. It is a weighty book – both in terms of its length (at 588 pages) and its significance. As a Secwépemc person who teaches Indigenous Studies and history, the impact of this book has been both personal and scholarly. On a personal level, seeing family members’ names and faces threaded throughout this work was a deeply emotional experience. From an academic perspective, this book offers a remarkable breadth and depth of information on the Secwépemc peoples, unrivalled elsewhere. Few Indigenous communities are lucky enough to have what the Secwépemc people now have: a comprehensive volume of the history, language, culture, and laws of our people – steeped in the rich, multidisciplinary materials of archaeology, Indigenous oral tradition, ecology, linguistics, geology, anthropology, and history. Representing 10,000 years of Secwépemc presence in the Interior plateau region of British Columbia through Indigenous perspectives, sources, and approaches, Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws will not only become known as the Secwépemc encyclopedia, but also sets the new gold standard for Indigenous scholarship.

Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws is organized into fourteen largely chronological and thematic chapters, each which explore a remarkable range of topics including: ancient Secwépemc history – including oral histories, population fluctuations, and changes to the land (Chapters 1 to 3); language (Chapter 4), Secwépemc resource use, stewardship, and trade (Chapters 5 and 6); Secwépemc sense of place, geographies, and boundary maintenance (Chapters 7 and 8); kinship, political organization, and spirituality (Chapters 9 to 11); and colonial change and Indigenous resistance (Chapters 12 and 13). This work easily stands to replace well-worn copies of James Teit’s 1909 ethnography The Shuswap vol. II, part VII – a valued resource that, until now, was the most in-depth source of Secwépemc historical accounts and oral traditions – but one deeply implicated by the damaging tradition of salvage ethnography. For many Secwépemc, and other Indigenous peoples, settler-produced ethnographies like Teit’s were the main (if imperfect) entry point into understanding our history and culture. But now we have an alternative.

While Teit and his contemporaries attempted to salvage pre-contact societies, later histories focused intently on contact and its implications. The Ignaces, however, reject this binary. This is not a romanticized narrative of a pre-contact past, nor is colonialism the centre point around which everything is oriented. Instead, as the title suggests, Secwépemc people, land, and laws (in their varied expressions across time and space) are the focal point here, and while the Ignaces do not ignore the change wrought by European contact and settler expansion, they refuse to define Secwépemc peoples in either idealized (and ultimately inaccurate images) or purely in relation to colonial agents.

In both content and approach the authors offer an impressive example of decolonized, collaborative, community-engaged work. Significantly, they prove – beyond doubt – that so-called western and Indigenous knowledge can easily co-exist. In Chapter 2, for instance, the Ignaces “present a composite picture of ancient past events between 11,000 and 3,500 years ago, based on converging lines of evidence from earth science, paleoecology, and linguistics, triangulated with Secwépemc oral histories and with archaeological information…” (31). They expertly demonstrate how geological evidence of a “single cataclysmic event” 9,750 years ago (which saw a Fraser River ice dam break and reverse the flow of the Thompson River system), is likewise documented in stsptékwll (Secwépemc oral traditions). There is no either/or account here – where Indigenous knowledge is judged for its accuracies – but rather a synergy of information from different but equal sources and epistemologies. Further, geological change is not merely linked to natural events, but through stsptékwll, we learn of the role ancient transformers had on shaping Secwépemc landscapes as well. Through all of this the authors unapologetically reject the false subjective/objective, western/Indigenous binaries and hierarchies that have trailed Indigenous ways of knowing for generations.

The Ignaces also demonstrate what’s possible when Indigenous peoples write their own histories using their own generations of situated knowledge, their own languages, customs, and means of passing knowledge between generations (in addition to existing non-Indigenous tools). Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws represents community-engaged research at its best. The pages are thick with oral traditions, as well as contemporary and historical reminiscences from almost one hundred and fifty Secwépemc peoples representing each of the seventeen communities (though some of communities are naturally more well-represented due to the authors’ connections and knowledge bases, as well as the existing records). This inspiring oral history research reflects a lifetime of work with Secwépemc narrators and highlights the kinship and community relationships. Importantly, in these pages, Secwépemc peoples are not mere sources of information, mined for their academic and cultural capital, but equal partners, directing the nature and outcomes of this research. The Ignaces’ collaborative and multidisciplinary approach is likewise mirrored in academic partnerships and co-authorship with archaeologist Mike K. Rousseau, ethnobotanist Nancy J. Turner, and geographer Kenneth Favrholdt, who bring essential insights to discussions of Secwépemc archaeological traditions, resource use, and trading practices.

The extraneous materials, which include images of landscape, physical formations, archaeological artifacts, and peoples, as well as maps, genealogies, and archival materials, transport the reader, offering an in-depth look at the changing landscape of Secwepemculcw throughout geological shifts, migrations, warfare, trade, and colonial encounter. I was especially struck by the authors’ discussions of Secwépemc nationhood and boundary maintenance (Chapter ![]()