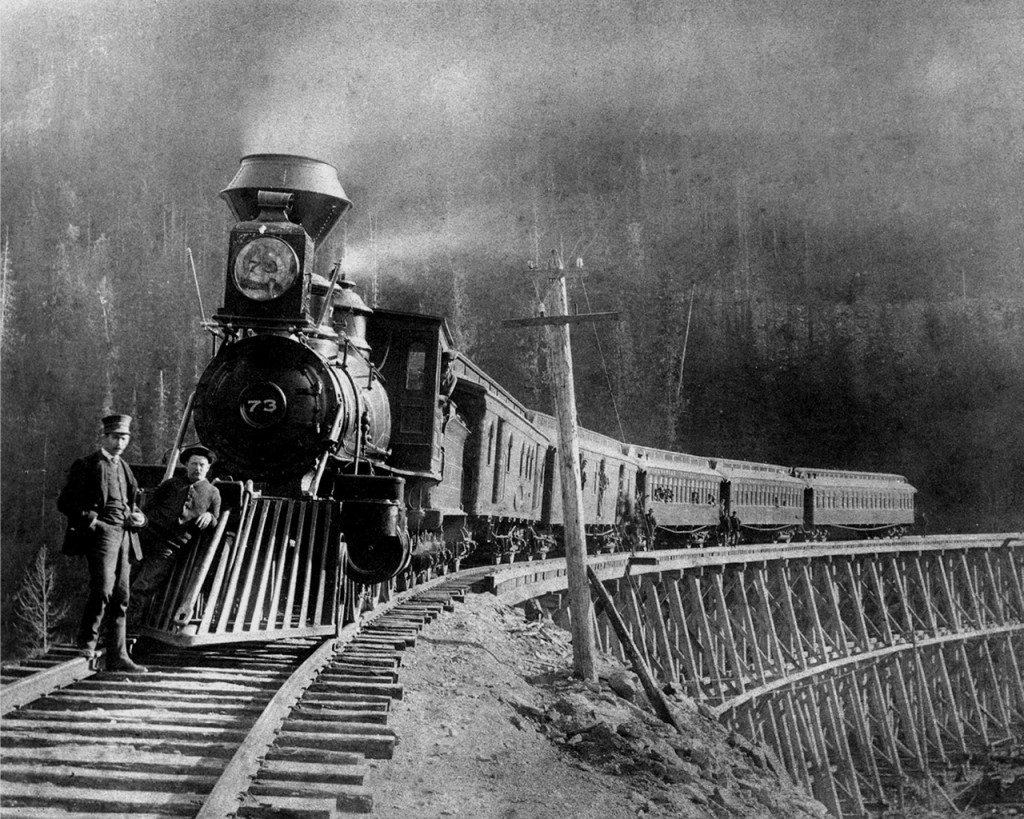

Passenger train heading to Notch Hill, Credit – CPR Archives

Just prior to completing the final revisions and additions to the last chapter of Everything Shuswap about the history of settlement, I rediscovered some material about the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) through the Shuswap in my history file cabinet. These papers were obtained during a visit to the CPR archives in Montreal back in 1988, when my focus was on local history. The information was significant enough to warrant including some excerpts to the chapter.

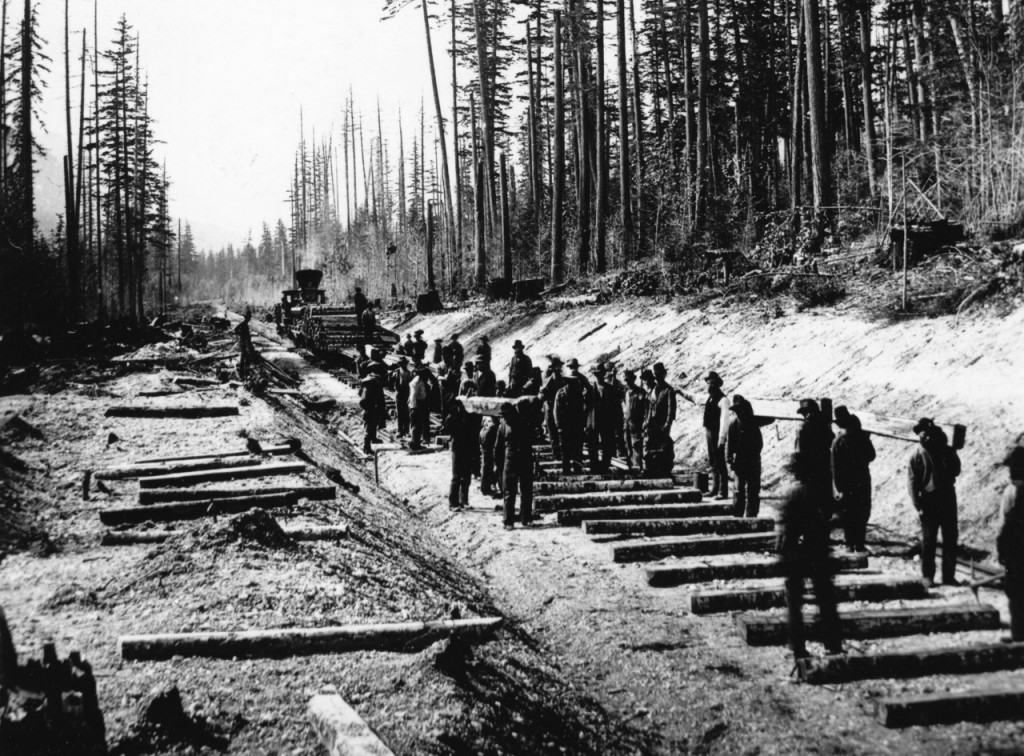

The building of the CPR was key to British Columbia joining Confederation and it was an essential part of nation building for Canada. It was a monumental task to construct the railway through the mountains and over the many canyons and waterways and much of it was accomplished with hand labour. William Cornelius Van Horne, who later became CPR president, was in charge of the project. There were two major contractors in B.C., Andrew Onderdonk in the west and James Ross in the east.

The building of the CPR was key to British Columbia joining Confederation and it was an essential part of nation building for Canada. It was a monumental task to construct the railway through the mountains and over the many canyons and waterways and much of it was accomplished with hand labour. William Cornelius Van Horne, who later became CPR president, was in charge of the project. There were two major contractors in B.C., Andrew Onderdonk in the west and James Ross in the east.

The SS Skuzzy II was instrumental in the construction by delivering supplies to the crews

This telegram provided a lower estimate of $17,447.41 per mile

It was not until the summer of 1884, that work began on the section between Savona and Chase Creek under the supervision of Henry Cambie and to the east, by Major A. B. Rogers. In early September, Van Horne wrote a letter to the CPR directors outlining the status and estimated cost of the project:

“The section to Griffin Lake, at the summit of Eagle Pass (113 miles) is estimated to cost not more than an average of $16,000 per mile, making the average cost per mile from the west end of Kamloops Lake to Griffin Lake, a distance of 128 miles, $21,565 dollars per mile. “

A November 1, 1884 handwritten letter from Andrew Onderdonk, an American construction contractor for the railway, to W.C. Van Horne provided even more description:

“At Salmon River, I found 7 gangs of Chinamen working on the fill, which will be finished in about 2 weeks. The work was well advanced. The bank is quite heavy, about 1½ miles long and in some case 16 feet high. When this is done some of these Chinamen will work at a heavy earth cut all winter 8 miles west of Salmon River and the balance be sent to the rock work west of the Summit. Sinclair was building winter quarters for five gangs of white men to work on this rock and by this time I think the men have gone up being about through on the Kamloops Lake.

I found the two tunnels 3 and 8 miles west of Chicamose [Sicamous] well stocked with flint, powder and provisions sufficient to complete the tunnels with their approaches…..

Bray has three gangs of white men, all first class. I think his tunnels are sure to be finished in April.” [ There were approximately 30 men in a gang.]

The book Van Horne’s Road by Omer Lavallée describes how there was a warehouse and store for the “Chinese” at the west end of Shuswap Lake and a smaller store for the “whites” in Blind Bay. Once the excavation work was done and the bridges and trestles were completed, the actual laying of the track progressed quickly at the rate of one mile per day.

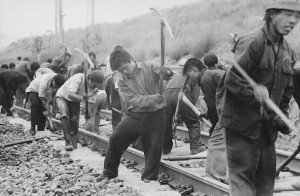

Laying track in the Fraser Valley, Credit – CPR Archives

This book also provides some other interesting details:

“The hot and dry midsummer of 1885, which had so much trouble with forest fires in the Selkirks, produced the same effect in the Shuswap region. A stockpile of ties, estimated to number between 12,000 and 15,000 was completely consumed as the railway was being built eastward from Kamloops in July. As a result, when the railway was advancing over Notch Hill and even though new ties were being delivered to replace those lost, the supply was far behind the demand.

Major Rogers noted with dismay that only half the required number of ties were being placed in the track, in order not to impede tracklaying. Ties were thus laid on a 42-inch spacing, rather than the specified 21-inch spacing.

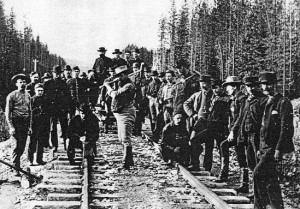

The delays in construction in the Selkirks in the summer of 1885 put Ross far behind schedule, and Onderdonk completed his section first. On September 28th, 1885 ran out of rails two miles west of the north fork of the Eagle River, on the west slope of Eagle pass. Ross’ forces were still 43 miles to the east, about five miles west of Albert Canyon.”

Onderdonk dismissed his employees on September 26, 1885, while Ross continued work until the last spike was driven on November 7th at Craigellachie.

POSTSCRIPT

Here is an excerpt from the Wikipedia article about the CPR concerning the treatment of the Chinese workers:

Many thousands of navvies worked on the railway. Many were European immigrants. In British Columbia, government contractors hired workers from China, known as “coolies“. A navvy received between $1 and $2.50 per day, but had to pay for his own food, clothing, transport to the job site, mail and medical care. After 2½ months of hard labour, they could net as little as $16. Chinese labourers in British Columbia made only between 75 cents and $1.25 a day, paid in rice mats, and not including expenses, leaving barely anything to send home. They did the most dangerous construction jobs, such as working with explosives to clear tunnels through rock.[15] The families of the Chinese who were killed received no compensation, or even notification of loss of life. Many of the men who survived did not have enough money to return to their families in China, although Chinese labour contractors had promised that as part of their responsibilities.[16] Many spent years in isolated and often poor conditions. Yet the Chinese were hard working and played a key role in building the Western stretch of the railway; even some boys as young as twelve years old served as tea-boys. In 2006 the Canadian government issued a formal apology to the Chinese population in Canada for their treatment both during and following the construction of the CPR.[17]

A typical camp scene

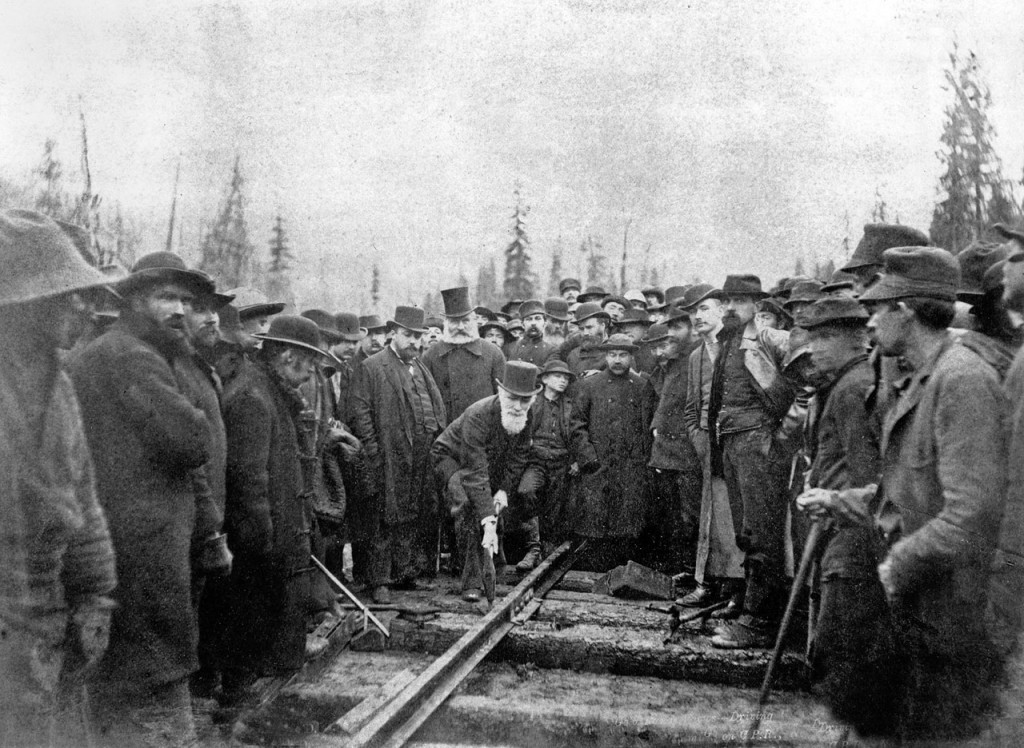

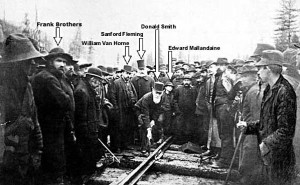

Workers staged their own “Last Spike” ceremony on Nov. 7th, 1885

Workers staged their own “Last Spike” ceremony on Nov. 7th, 1885