Old pit-house near Spences Bridge

The number of photos taken of the Secwepemc people increased at the end of the 19th century due to the efforts of the American Museum of Natural History. Morris Jesup was president of the museum and he financed an extensive expedition to study the cultural, racial and linguistic attributes of Indigenous peoples living in the North Pacific Region. His goal was to gather evidence to support the Bering Strait migration theory, which postulated that the North American continent was populated by the migration of Asian peoples across the strait.

the museum and he financed an extensive expedition to study the cultural, racial and linguistic attributes of Indigenous peoples living in the North Pacific Region. His goal was to gather evidence to support the Bering Strait migration theory, which postulated that the North American continent was populated by the migration of Asian peoples across the strait.

The expedition began in 1897 and spread out across British Columbia, Alaska and Siberia. Because many northern Indigenous peoples were being decimated by diseases, members of the expedition also believed they were making final records of vanishing cultures. In addition to observing local social practices, they made wax-cylinder recordings, collected artefacts, amassed data on physical looks, and took many photographs.

In 1894, anthropologist Franz Boas, stopped off in Spence’s Bridge during one of his ethnographic field trips where he met James Teit and instantly recognized his potential as an ethnographer who was not only fluent in the local Nlaka’pamux (Thompson) language, but also had close ties to the local Indigenous people. Teit worked for the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, serving as Boas’ guide and writing three essential ethnographies on the Nlaka’pamux, the Lillooet and the Shuswap.

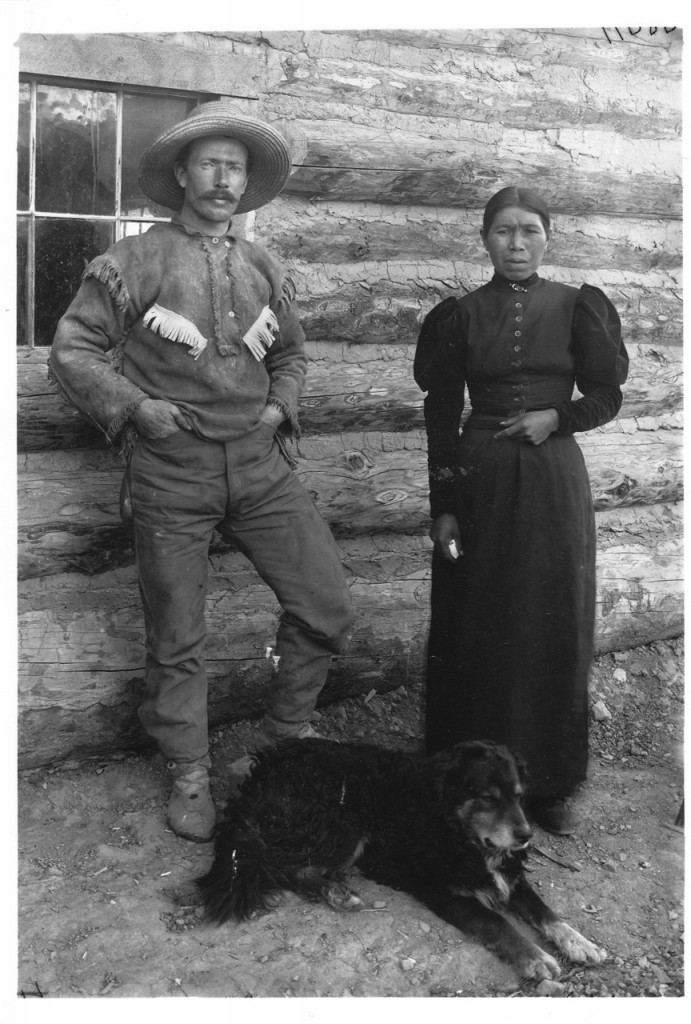

One of the first photos from the Jesup expedition was taken in 1897 at Spences Bridge of James Teit and his first wife, Lucy Artko. The photographer was Harlan Smith, who was the leading archaeologist for the expedition. There were four images taken in 1898 and 1899, one of a woman dressed traditionally with baskets and a digging stick and another of a woman scraping a hide. There is also a photo of an old pit-house in the Nicola Valley and a summer dwelling that looks like a tepee constructed with walls of bark or wood.

There are a few amazing photos of Nlaka’pamux in traditional clothing, all taken at Spences Bridge. One is of a warrior with long braided hair holding a pipe and wearing a feathered headdress, a bear-claw necklace, a fur-covered hide vest, and rawhide pants. The others are of Nlaka’pamux people posing next to a teepee made of woven mats in traditional clothing suitable for a celebration.

Teit took the warrior shot likely in 1897 and Valient Vincent took the others in 1910. After his work with Teit, he owned the King Photo Studio in Vancouver. There were many similarities between the two Indigenous nations, thus these photos provide a helpful perspective on the Secwepemc. In the late 1800s, Indigenous people primarily wore western clothes, so it is significant that they were able to either hold onto their traditional clothes or make replicas.

Although the Jesup Expedition did not produce data that proved the Bering Strait theory, it provided a wealth of information on the variations and connections between the Indigenous populations on both sides of the Pacific that scholars still use today. It was also able to show that culture, language and race varied independently, which was a radical departure from White-supremacist theories of early 20th Century Europe and America.

All these images are held by museums and the process to obtain the rights and the digital files is costly and time consuming. Our request for assistance from the provincial ministry resulted a letter from the Royal BC Museum reiterating its policy to charge for photos for books that will be sold to the public. They do not recognize the non-profit nature of the Everything Shuswap book project in which the proceeds from book sales will go to support outdoor learning for the school district.

If only our Canadian heritage institutions could follow the lead of the New York Public Library, which recently released 180,000 high resolution historical photos and documents on their website and invited users to remix them. (see New York Public Library releases archival photos and docs)

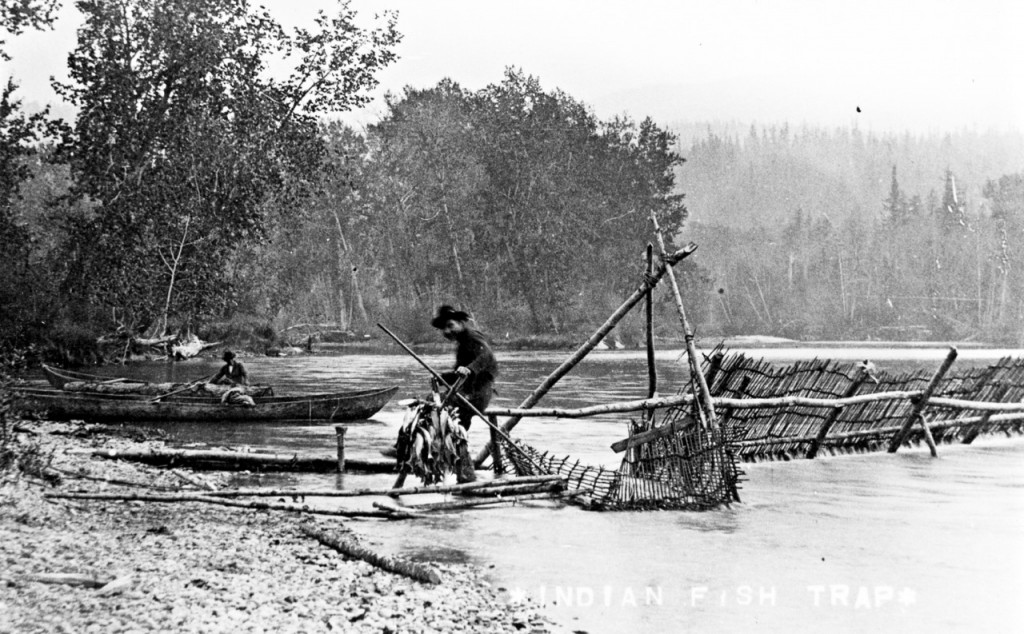

photo courtesy of Enderby and District Museum and Archives

As a postscript to the last column, there are three more excellent images taken in 1891, all provided without charges from the Enderby Museum. One shows a large weir fish trap on the Shuswap River and one man with a sling of fish and another in a dugout canoe. Another shows a fish camp on the river with racks of drying salmon. And another shows 14 men, some posing with rifles and 4 women, waiting for the game warden.

photo courtesy of Enderby and District Museum and Archives

POSTSCRIPT

Experts have criticized the value of the images taken during the expedition because many of the photos were staged by the photographers. Given that traditional dress was not worn then and few Indigenous people were still engaged in traditional activities, it is obvious that many of the scenes were set up. Nonetheless, the images still provide an idea of how Indigenous people would have dressed and what they did. In 1928, Harlan Smith made a silent film called, The Shuswap Indians, which I hope to get soon and plan to write about as well.